September 29, 2012

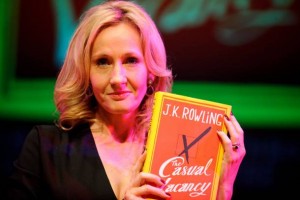

So was it worth all the hype? Did it merit an embargo so strictly enforced that anyone outside the author’s immediate family didn’t see the book until 8am this Thursday? And after seven Harry Potter adventures, did The Casual Vacancy reveal that JK Rowling had finally grown up?

Well, to answer the last question first, the subject matter in Rowling’s first adult novel is certainly grown up. To the best of my memory, the 450 million fans who bought the Harry Potter saga never encountered their young hero on a school bus “with an ache in his heart and in his balls” after placing a satchel over his crotch to conceal an erection.

Nor, so far as I can recall, did Hermione’s dressing gown fall open to reveal “the contours of her big breasts as they rested on her forearms”. And I’m pretty sure that neither she nor her young chums used those naughty words beginning with “f” and “c” which are liberally strewn throughout this book.

You can almost sense the glee of an author, who has always seemed as prim as her young heroes and heroines, opting to abandon the basic proprieties that must be observed in the writing of children’s fiction. “He climbed on top of her”, she relates of a middle-class boy who’s in bed with a socially deprived girl. “This, he knew, was real life”.

Rowling knows it, too, and has written a very contemporary novel for those readers who were always too old to be enchanted by tales of teen wizards locked in perpetual battle with the forces of darkness. Here the forces of darkness reside in a small West Country town – families who are pillars of smug respectability and who deplore the nearby presence of a sink estate with all its human detritus. The book’s main plot concerns their efforts to rid themselves of this drug-infested, welfare-supported blot on their landscape.

From the outset it’s clear where the author’s sympathies lie. Before she became a zillionaire, Rowling had grown up unhappily in one such West Country town and, after a failed marriage, had arrived clinically depressed in Edinburgh and had depended on social welfare to see her through bad economic times as she worked on her first Harry Potter book.

And thus she writes with real feeling about the inhabitants of the sink estate, especially the teenage Krystal, troubled and fractious daughter of a drug-addicted prostitute. And it’s Krystal’s involvement with the son of the town’s deputy headmaster that leads to the deaths with which the book finally strives for tragic resonance.

I’m not convinced it succeeds in that aim because the author has been having too much fun skewering the town’s middle-class families, almost all of whom are quite ghastly in their snobbery, narrow-mindedness and hypocrisy. There’s a wonderfully awful dinner party during which the host and his privileged guests become parodies of Daily Mail readers as they rail against the “addicts and wasters” who live in the sink estate – regarding the plight of these unfortunates as merely a matter of not taking “personal responsibility” for their lives (Rowling’s original title for the book was Responsibility).

And there’s an even funnier birthday party scene towards the end, during which pent-up tensions (caused by anonymous and malicious website postings) and the intake of too much drink lead to sexual indiscretion, social embarrassment and angry confrontations.

The book has failings. Rowling’s prose is functional at best, though she’s very good at dialogue and occasionally comes up with an arrestingly pithy line, as in her dry observation that the deputy headmaster was “perenially appalled by the threadbare state of other people’s morals”.

At more than 500 pages, it’s also too long and with an abundance of characters who are too alike in their smug certainties, vacuities and hypocrisies. Pompous delicatessen owner Howard and his shallow do-goodery wife are recognisably insufferable types, so do we really need lengthy sections about Howard’s son and daughter-in-law, who are lampooned for much the same deficiencies? And a couple of the characters (solicitor Gavin in particular) are so uninteresting that the author should have excluded them.

But there’s a real fizz to the comic set pieces I’ve mentioned, while you get genuine engagement and insight when Rowling focuses her attention on the book’s teenage characters, whether they be disaffectedly middle-class or products of an alienated underclass. Well, as millions of Harry Potter fans will readily testify, she knows her young people and the dreams they harbour.